viernes, 23 de abril de 2021

Qué es Madrid

https://www.huffingtonpost.es/entry/madrid-4m-radiografia_es_60771e5de4b0293a7edd5eda

19/04/2021

Qué es

Madrid

4-M: radiografía de una comunidad que se ha

convertido en la locomotora económica de España en la que campa a sus anchas la

desigualdad.

Antonio Ruiz Valdivia

“Madrid, en expresión del interés nacional y

de sus peculiares características sociales, económicas, históricas y

administrativas, en el ejercicio del derecho a la autonomía que la Constitución

Española reconoce y garantiza, es una Comunidad Autónoma que organiza su autogobierno

de conformidad con la Constitución Española y con el presente Estatuto, que es

su norma institucional básica”.

Así se define la propia Comunidad en el

artículo uno de su Estatuto. De manera muy madrileña, sin preámbulos, directa,

sin hablar de naciones o realidades nacionales, pero dejando claro que es algo

“peculiar” y con los rasgos que la marcan: su sociedad, su economía, su

historia y la administración. Una autonomía que estuvo también a punto de no

serlo, ya que en los debates previos se barajaron otras opciones como su

inclusión dentro de Castilla-La Mancha o la creación de un gran distrito

federal, mirando como espejos a México o Washington.

Al final, Madrid se encajó como comunidad, no

aprobándose su Estatuto hasta el año 1983 -el último junto a Castilla y León-,

ya que no tenía ni órgano preautonómico. Una historia muy diferente a la de

hoy, en la que se ha construido con los años esa imagen de autonomía, esa

identidad como unidad dominada desde el año 1995 por el Partido Popular. Desde

entonces se ha venido trabajando por un modelo de corte neoliberal, en el que

la administración intenta presentarse como palanca económica del sector

privado. La propia web de la región lo dice tal cual: “Un Gobierno Regional

dedicado a la mejora continua del clima de negocios y atento a las necesidades

del inversor”.

Madrid es hoy por hoy la gran locomotora

económica del país, un título que arrebató hace tres años a Cataluña, lastrada

por el proceso independentista. Según los datos del INE, el PIB de Madrid cerró

en 2019 con un valor de 239.878 millones de euros (el 19,3% del PIB nacional)

frente a los 236.739 millones de euros de Cataluña (19%). Los madrileños

también son los más ricos de los españoles, con un PIB per cápita situado en

35.876 euros por habitante (lo que supone un 35,7% más de la media nacional,

que estaba en 26.438 euros).

Una historia de riqueza, lujo… y mucha

desigualdad. Dentro de la propia autonomía se notan las diferencias. Figuran

algunos de los municipios más ricos de España, llenos de mansiones y coches de

lujo, como Pozuelo, con una renta media de 79.506 euros, seguido de Boadilla

del Monte (61.910 euros), Alcobendas (60.842 euros) y Majadahonda (54.506

euros), según datos de la Agencia Tributaria. Unas cifras que marean a los

núcleos en la cola, como Cenicientos (18.818 euros), Villaconejos (19.707

euros) y Estremera (20.430 euros).

Una autonomía en la que cada día es más

patente la diferencia entre clases. Según el Informe FOESSA presentado por

Cáritas, la desigualdad entre el 20% de los más ricos y el 20% de los más

pobres en Madrid es la más alta en toda España. Un millón de personas está en situación

de exclusión social en la región (el 16,2% de la población). De ellos, 490.000

están en “exclusión severa”: acumulan tantos problemas en la vida diaria que no

tienen la oportunidad de construir un proyecto vital estructurado. En los

últimos diez años, la renta media de la población ha crecido un 2%, mientras

que entre los más pobres ha bajado un 30%. Y como gran causa de exclusión

social: la vivienda.

En Madrid hay datos durísimos, como recoge el

informe, como que existen 167.000 hogares en situación de hacinamiento, 315.000

hogares se quedan por debajo del umbral de la pobreza severa una vez se han

pagado los gastos de vivienda y 219.000 hogares están en situación de vivienda

inadecuada. Una realidad que no se quiere visibilizar en las grandes campañas,

y que lleva a que en 161.000 hogares se haya dejado de comprar medicinas,

seguir tratamientos o dietas por problemas económicos. Unas diferencias

económicas y sociales que se dejan ver incluso hasta en la esperanza de vida,

de hasta diez años entre barrios dentro de Madrid capital (la media de

esperanza en Amposta -San Blas- es de 78,4 años frente a los 88,7 del barrio de

El Goloso -Fuencarral/El Pardo).

¿Y a qué se dedica Madrid? Según los datos

proporcionados por la Comunidad de Madrid en su portal, el 87% del valor

añadido bruto es por el sector servicios. A nadie le puede extrañar la campaña

por los bares y la apertura de comercios lanzada por Isabel Díaz Ayuso

(buscando esos millones de votos). Por detrás, con una distancia brutal están

otros sectores: industria (8%) y construcción (5%).

“Madrid es la almendra de la M-30 y el

aeropuerto. Vive de esto. También tiene las grandes sedes de las

multinacionales. Tiene una conectividad con América Latina. La ciudad funciona,

con Carmena o con Almeida”, explica el economista José Carlos Díez sobre el

modelo económico imperante. “La parte privada funciona muy bien”, añade, para

luego decir que le falta “un plan”: “Las universidades no están bien dotadas,

la parte del ecosistema de innovación tampoco, tiene mucho más potencial de lo

que se aprovecha”. “Debería aspirar a ser un gran hub digital europeo y mundial, atraer más nómadas europeos y

empresas del mundo digital. Y debería ser más generosa y compartir más con el

resto de España. No tiene gran sentido que lo centralices todo cuando eres un

gran hub de servicios que vive del

resto de España”, concluye, para luego apreciar que cree que el ‘sorpasso’ a

Cataluña se debe más por el procés que por los méritos de Madrid.

La comunidad tiene también ese efecto

“capitalidad” de la que se quejan otras autonomías. Decir Madrid es decir poder

en un Estado muy centralizado. Todas las grandes instituciones están en la

villa y corte: desde la corona hasta el Gobierno pasando por las Cortes

Generales, los grandes tribunales y hasta las grandes empresas públicas. Esto

hace también que el sector privado se decante por la comunidad (los principales

bancos tienen sus cuarteles generales como el Santander, el BBVA, Bankinter y

el Popular, al igual que el mundo financiero con la Bolsa y el Ibex). Se sitúa

como la cuarta ciudad europea con sede de multinacionales, después de Londres,

París y Ámsterdam, según la lista FORTUNE Global 500.

Esto lleva a que muchas veces Madrid se crea

el centro del país, el centro del debate, creándose una burbuja que no tiene

mucho que ver con el resto de la nación. La politóloga Ana Sofía Cardenal lo

explica así: “Madrid juega un papel importantísimo porque es la capital

política y porque hoy es un motor económico. Siempre ha concentrado a todas las

instituciones del Estado, esto no ha cambiado, pero hoy sabemos que tiene una

capacidad de atraer inversiones. Ahora ya es motor económico, que no lo había

sido tradicionalmente”.

“Esta cosa de Madrid como modelo económico

tiene un efecto polarizador territorial. Madrid tiene un Estado detrás, y

Barcelona, no. Esto puede hacer hasta más difícil arreglar el problema

territorial”, considera, antes de incidir en que en la comunidad el Partido

Popular tiene “su laboratorio”. “Pero esto puede ser contraproducente porque

puede hacer que otras comunidades -en esto ha estado Cataluña siempre sola- se

alíen para hacer contrapeso. Hace falta hacerlo”, agrega.

Esto, por ejemplo, ya se ve en que en el

Parlamento hay partidos de la periferia que “se siente olvidada”, añade. “Esto

podría ir a más y fortalecerse”, continúa esta politóloga. “Madrid no es

España”, subraya Cardenal ante esa burbuja de políticos y medios. Y hace una

reflexión: “En Madrid el PP es hegemónico, pero el Gobierno central es de

izquierdas y se apoya en partidos de ámbito periférico territorial. Esto te

demuestra que Madrid no es España. Esto podría acabar consolidándose”. “El PP

no puede exportar este modelo a otros territorios porque no tienen la riqueza

de Madrid, ese efecto capitalidad”, hilvana la politóloga y profesora de la

UOC.

En el estado autonómicos, las comunidades

tienen dos columnas principales en la gestión del Estado del Bienestar: la

sanidad y la educación. Madrid, según el último informe del Ministerio de

Sanidad publicado en marzo de este año y con datos de 2019, es la segunda que

menos gasta en sanidad por habitante (1.340 euros). En concreto, se destinaron

de las arcas públicas 8.962 millones de euros, un 3,7% del PIB. Es el

porcentaje más ínfimo de las autonomías (la media nacional es del 5,6% y, por

ejemplo, Extremadura dedicó un 8,6%).

En Educación también está a la cola en el

gasto medio por alumno. Según los últimos datos del Ministerio de Educación, en

la Comunidad de Madrid se sitúa en 4.593 euros por estudiante no universitario

en la región, mientras que el País Vasco (líder en este sector) se superan los

9.000, el doble.

Ellos son el futuro de una comunidad, que ahora

tiene una media de edad de casi 42 años y que envejece cada día más (en 1998 la

media estaba en los 38 años). Uno de los factores claves para intentar

rejuvenecer la región es la inmigración. En el último informe de población

extranjera -actualizado a enero de 2020- se recoge que el 15% de la población

es de nacionalidad extranjera (1.026.33 de los 6.877.957 ciudadanos). La medida

de edad de los nacidos fuera es de 34,9 años y los sietes grupos con más

presencia son los rumanos (18,2%), marroquíes (8,2%), chinos (6,4), colombianos

(6,2%), venezolanos (6%), peruanos (4,2%) e italianos (4%).

Una radiografía de Madrid en la que hay que

detenerse también en la religión, con una Iglesia que siempre ha tenido un

enorme peso en esta comunidad. Según el último estudio del Centro de

Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS), ahora mismo el grupo que predomina es el de

los agnósticos/indiferentes/ateos, que representan el 38,7%, por delante de los

católicos no practicantes (38,5%), los católicos practicantes (18,2%) y los

creyentes de otras religiones (2,9%).

Madrid, ese magma, ese rompeolas de todas las

Españas. Esa burbuja que tiene que ir ahora a votar.

jueves, 22 de abril de 2021

Clases orales

CURSO 2017-2018

https://primerobachhistoria.blogspot.com/2018/04/diario-de-clase-06042018.html

https://drive.google.com/file/d/10w2NrIOJ-g9yRLJuinPg0oLl-XHVc15m/view

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qyKpIHvlnRw

https://primerobachhistoria.blogspot.com/search/label/0%20Diario%20de%20clase%20con%20audio

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47w2Y314Q0k

https://primerobachhistoria.blogspot.com/2017/11/diario-de-clase-29-11-17.html

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZASrDb8-C_A7ZUPbfzSCCrNungKpQR8g/view

miércoles, 21 de abril de 2021

Roman Heavy Cavalry (2) AD 500-1450

Plate A. THE 6th CENTURY

Lámina

H. LOS SIGLOS XIV-XV

(1)

Katáphraktos, asedio de Vodena, 1351

Reconstruido

en gran parte de una pintura en la catedral de Edesa (antigua Vodena, Macedonia).

Su casco, de un ejemplar hallado recientemente en Anatolia, plantea una duda

acerca del origen de muchos cascos nómadas, y sobre el intercambio de

materiales militares cumanos y romano orientales. La armadura corporal incluye

una gorguera usada con un klivánion en el cual las petala (láminas) están

dispuestas para formar un disco central, típico de la armadura turco-mongola

del periodo; la forma de ese coselete era claramente de inspiración oriental.

Para las otras partes de la armadura debemos imaginar una disposición regular,

como un ejemplo con el mismo tipo de escamas en la representación del siglo XIV

de San Trofimos en la iglesia de Decani; obsérvese también el pequeño escudo

circular. Las armas ofensivas son una lanza de caballería, una espada, un arco

compuesto y una maza. Podemos suponer que esta era la apariencia de los “100

jinetes catafractos locales” mencionados por Cantacuzeno en el asedio de Apros

en 1322.

Roman Heavy Cavalry (1) CATAPHRACTARII & CLIBANARII, 1ST CENTURY BC–5TH CENTURY AD

https://forums.taleworlds.com/index.php?threads/best-dressed-warrior.51090/page-431

Early

Armored Cavalrymen

(1)

Romano-Egyptian heavily armoured cavalryman, 31 BC.

This

figure is copied from part of the famous monument to a senior naval officer of

the time of Marcus Antonius, now in the Vatican museum, and from the Mausoleum

of the Titeci near Lake Fucinus. He probably represents a member of the kataphraktoi

of the Eastern allies of Cleopatra and M. Antonius, or perhaps even a member of

their bodyguard. Note the helmet with wide cheek-guards partly protecting the

face; the thorax stadios (‘muscled’ or anatomical) cuirass; the shield of scutum

type, and the three javelins. Hidden here, his right arm would be covered with

articulated ‘hoop’ armour.

(2)

Romano-Thracian cataphract; Chatalka, c. AD 75−100

The

armoured cavalryman from the Chatalka burial in Bulgaria may have worn what Arwidson

calls ‘belt armour’ – a combination of iron plates, scales and splints in the

Iranian tradition. The neck is protected by a thick iron gorget, following the

Thracian–Macedonian style; it was made in two pieces connected by a strap, and

the outer surface was originally painted red. Surviving individual rings show

that it was worn over a separate ringmail collar. Note his magnificent masked helmet

(see reconstructions on pages 8-9). The Chatalka burial also included a

beautiful sword of Chinese type.

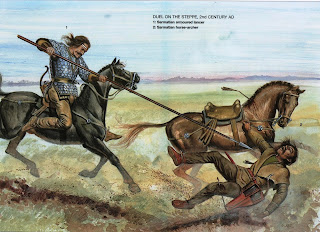

Early

Units, 2nd Century AD

(1)

Sarmatian cataphract; Adygeia, c. 110 AD

Archaeological

finds at the Gorodoskoy farm site on the ancient Pontic steppes in Adygeia

(Russian Federation) revealed the impressive armour of a true Sarmatian cataphractus,

a prototype for the Roman armoured contarius. He wears a segmented iron

spangenhelm with an attached scale aventail; the skull consists of four

vertical pieces with the space between filled with horizontal strips, as

depicted on Trajan’s Column. The height of the occupant of the grave was about

1.7m (5ft 6in), and the superb ringmail coat was up to 1.5m long (4ft 11in). At

the top it fastened with buckles to the scale aventail. At the bottom it was

divided into two flaps, allowing the wearer to sit on a horse with ease; the

flaps were wrapped around the legs like trousers, being fastened in this position

above the knee and on the shins with wide ringmail strips. Because of the poor

preservation of the recovered armour the length of the sleeves is not clear,

but given the degree of easy movement that would be required to wield the swords

and javelins found in such graves we assume that they ended at the elbows. He

carries a long spatha-type sword, but his main weapon is the very long contus

sarmaticus.

(2)

Decurio of Ala Prima Gallorum et Pannoniorum catafractata, 2nd century AD

The

reconstruction of this junior officer is based on the studies of Gamber. He

proposes that the chamfron found at Newstead, Scotland, and other recovered

fragments of leather horse armour decorated with rivets, give an idea of the

appearance of the mounts used by the early Roman cataphracts. The decurion’s

personal armour is reconstructed from Pannonian gravestones and archaeological

finds; the troopers also could wear decorated helmets like this Trajanic or

Hadrianic example from Brza Palanka, and bronze ocreae (greaves). We have completed

him with full-length ‘hooped’ articulated arm protection (the galerus), a

cavalry spatha and the contus.

(3)

Praefectus of an Ala catafractata, late 2nd century AD

This

unit commander is largely reconstructed from the horseman balteus decoration

from Trecenta in the Veneto region of northeast Italy. The officers of the

cataphracts wore beautiful decorated helmets of Hellenic taste, here copied

from an open-mask specimen ex-Axel Guttman collection (AG451). He is wearing a composite

armour formed by a thorax stadios and laminae vertically disposed around the lower

trunk, following the system of the Iranian ‘belt armour’, and copper-alloy

greaves. Gamber proposes the mace as an officer’s weapon, which may be confirmed

by a specimen found in Dura Europos associated with cavalry finds, and by the

fighting position of the cavalryman represented on the Trecenta balteus

fitting. A regimental commander’s horse equipment would be suitably

magnificent; decorated pectoral protections with embossed figures, and partial bronze

chamfrons with eye-protectors, have been found near Brescia, Turin, Vienna and

in other localities.

First Half of the 3rd

Century AD

Primera mitad del siglo III

(1) Osrhoenian heavy cavalry

sagittarius, army of Severus Alexander; Gallia, AD 235

According to Herodian,

Severus Alexander had brought with him for his Rhine frontier campaign a large

force of archers from the East including from Osrhoene, together with Parthian

deserters and mercenaries. The horse-archers included heavy armoured units;

shooting from well beyond the range of the Germans’ weapons, they did great

execution among their unarmoured adversaries. We have given this soldier some

Roman equipment found in north German bogs, such as the mask helmet from

Thorsbjerg and the ringmail shirt from Vimose, integrated with clothing and

fittings from Parthian and Hatrene paintings. Iconography (e.g. synagogue

painting from Dura), and graffiti suggest that the composite bow and a quiver

would have been carried slung from the saddle behind the right leg, convenient

for the right hand.

(1) Saggittarius de caballería pesada de Osroene, ejército de Severo

Alejandro, Galia, 235

Según Herodiano, Severo

Alejandro trajo con él para su campaña en la frontera del Rhin una gran fuerza

de arqueros del este incluyendo de Osroene, junto con desertores y mercenarios

partos. Los arqueros a caballo incluían unidades fuertemente acorazadas,

disparando desde más allá del alcance de los germanos, causaban una gran

matanza entre sus enemigos sin armadura. Le hemos dado a este soldado algún

equipo romano encontrado en ciénagas de la Germania septentrional, como el

casco con máscara-visera de Thorsbjerg y la cota de malla de Vimose, integrados

con ropa y adornos de pinturas de Partia y Hatra. La iconografía (es decir la

pintura de la sinagoga de Dura), y los grafitos-graffiti sugieren que el arco

compuesto y la aljaba se habrían llevado colgados de la silla detrás de la

pierna derecha, adecuado para la mano derecha.

(2) Cataphractarius of Ala

Firma catafractaria, army of Maximinus Thrax; Germania, AD 235

Reconstructed from the stele

of the Saluda brothers, he has rich equipment from the Rhine area: a

Mainz-Heddernheim style helmet; bronze scale armour from Mainz; and highly

decorated greaves embossed with a representation of the god Mars, from Speyer.

His weapons and related fittings (spatha, baldric, contus) are copied from

finds around Mainz, Nydam, and the Vimose bogs, where a lot of captured Roman

equipment relating to the campaigns of Severus Alexander and Maximinus was

found. The armour of his horse has been reconstructed from the lesserknown

third trapper found in Dura Europos, made of copper-alloy scales, although the

prometopidion (chamfron) is from Heddernheim. Under it the horse wears the

equine harness from Nydam, including a brown leather muzzle with a bronze boss

and fastened with bridle-chains to the rings of the bit.

(2) Cataphractarius del Ala Firma catafractaria, ejército de Maximino

el Tracio, Germania, 235

Reconstruido de la estela de

los hermanos Saluda, tiene un equipo rico propio de la del Rhin: un casco de

estilo Mainz-Heddernhelm, armadura de escamas de bronce de Mainz; y grebas muy

decoradas grabadas con una representación del dios Marte, de Speyer. Sus armas

y adornos relacionados (spatha, tahalí, contus) están copiados de hallazgos en

la zona de Mainz, Nydam y os pantanos de

Vimose, donde fue hallado un montón de equipo romano capturado relacionado con

las campañas de Severo Alejandro y de Maximino. La armadura de su caballo ha

sido reconstruida del menos conocido tercer jaez-arreos encontrados en Dura

Europos, hechos de escamas de aleación de cobre, aunque la prometopidion

(testera) es de Hedderheim. Bajo ellos el caballo usa un arnés equino de Nydan,

incluyendo un muzzle de cuero castaño con un umbo de bronce y sujeto con unas

bridas formadas por cadenas a los anillos del bocado.

(3) Clibanarius of a Numerus

Palmyrenorum; Dura Europos, mid-3rd century AD

This ‘super-heavy’

cavalryman is reconstructed from the famous clibanarius graffito at Dura

Europos (Tower 17). Note his conical mask helmet, and laminated armour covering

torso, legs and arms. The limb defences consisted mainly of plates overlapping

upwards, as required to throw off enemy spears running up the left arm,

unprotected by a shield. Composite scale-and-plate armour similar to Iranian or

Palmyrene models, as portrayed in the graffito, covers the trunk. Thigh

protection was often associated with greaves, and was found at Dura made of

copper alloy and lined with linen. His mount is stronger than the usual Arab

breeds, and is protected by the iron-scale trapper – described in the text as

number (2) – found at Dura.

(3) Cibanario

de un Numerus Palmyrenorum, Dura Europos, mediados del siglo III

Este jinete “superpesado” está

reconstruido a partir del famoso graffito del clibanario en Dura Europos (Tower

17). Obsérvese su casco cónico con visera, y su armadura laminada cubriendo el

torso, las piernas y los brazos. Las defensas de los miembros consistían

principalmente en láminas solapadas hacia arriba, …

desprotegido por la falta de escudo. La armadura

compuesta de escamas y láminas parecida a modelos iranios o de Palmira, como la

retratada en el graffito, cubre el tronco. La protección de los muslos a menudo

estaba asociada a las grebas, y se encontraron en Dura hechas de aleación de

cobre y forradas con lino. Su montura es más fuerte que las razas árabes

habituales, y está protegido por los jaeces de escamas de hierro –descritas en

el texto como número (2)- encontradas en Dura.

Second

Half of the 3rd Century AD

(1)

Roman clibanarius, Dura Europos, AD 256

Reconstructed

after the finds from Dura, he and his mount are fully armoured in iron and

bronze (copper alloy). The openmasked helmet of Heddernheim typology, whose

fragments were found at Dura, is a very rare variant with double protones in

the form of eagles; it finds parallels only in a similar helmet formerly in the

Axel Guttman collection, and on late Roman coins. The iron ringmail shirt shows

rows of bronze rings trimming the ends of the sleeves and the skirt, and is

worn in combination with an articulated arm-guard (galerus) of laminated iron

plates. Each thigh is protected with a redlacquered leather παραμηρίδιος

(thigh-guard) as found in Dura; this had provision for laces to be fastened

around the thigh, and extended from the waist to below the knee, below which

the man wears bronze greaves. His main weapon is again the contus, this time carried

without a shield, and for close work a mace is slung from the saddle.

(2)

Draconarius of an Ala cataphractariorum; army of Galerius, late 3nd century

This

standard-bearer is reconstructed from the Arch of Galerius. The equipment of

the catafractarii on this monument shows the employment of both ‘ridge’ and

segmented helmets, typologically similar to specimens from Kipchak and

Kabardino-Balkarie. The lamellar copper-alloy cuirass incorporates decorated

iron plates fastening it on the chest, and is worn over a padded thoracomacus

furnished with two layers of thick pteryges. Note the employment of high boots,

the Egyptianmade tunic decorated with three sleeve stripes (loroi), and the military

sagum cloak. His draco is copied from the Niederbieber specimen; the Arch of

Galerius carvings represent this standard carried by cataphracts charging

against the Persians.

(3)

Roman cataphractarius of Ala I Iovia cataphractaria; Nubian borders, AD 295

Reconstruction

from the Roman statue today in the Museum of Nubia at Aswan, which probably

represents a trooper of this unit created by Diocletian (r. 284−305) and

stationed to safeguard the provincial borders of Aegyptus. The squamae covering

his body, arms and legs echo the armour of the Rhoxolani heavy cavalry depicted

on Trajan’s Column. The statue is headless; we have given him a spangenhelm

from Egypt today preserved at Leiden Museum, correctly reconstructed here with

the original nasal guard. The magnificent harness of his horse is taken from

the Late Roman horse trappings of the Ballana graves, contemporary to the Dominate

period.

First

Half of the 4th Century AD

(1)

Cataphractarius Valerius Maxantius

Valerius

is reconstructed after his funerary monument, which describes him as an

‘eq(ues) ex numero kata(fractariorum)’. He represents one of the heavy

cavalrymen formerly serving under Maxentius who, after Constantine’s victory,

were sent to patrol the north-eastern frontiers of the Empire. A strong Sarmatian

influence is visible in the scale armour, the padded long-sleeved under-armour

garment, and the boots, diffused among the Roman cavalry since the 2nd century.

His primary weapon is the contus, but he also wears a long spatha of Iranian

origin, copied with its belt from the precious specimen in the Újlak Bécsi út

grave near Aquincum (Budapest) in Pannonia. He carries a ridge-helmet of the

new typology introduced into the Roman Army during the Tetrarchy, and wears a

galericulum to absorb its weight and the force of blows to the head.

(2)

Centenarius Klaudianus Ingenuus of Numerus equitum catafractariorum seniorum;

Lugdunum, Gallia, c. AD 325−350

This

is copied from his stele, but its date is debatable, and perhaps as late as the

early 5th century. The hybrid pseudo-Attic ridge-helmet with its high crest

shows a red-orange plume, which is confirmed for the late Roman heavy cavalry

by a later mosaic at Santa Maria Maggiore. The other metallic parts of his

equipment are the lorica squamata and greaves, which are worn over leather

protection and boots, respectively. On his forearms note the decoration of his

embroidered túnica manicata, and his long cavalry sagum cloak has a fringed

edge. According to his gravestone his two calones (military servants) had a

javelin, a shield and a short sword.

(3)

Draconarius of Numerus equitum catafractariorum seniorum

The

paintings in the Via Latina catacombs, contemporary to the triumphal procession

of Constantius II in Rome, are an often-neglected source illustrating Roman

cataphracts. They show the use of old typologies of masked helmets, and the wearing

of the thorax stadios muscled cuirass (also attested among the Persian Sassanid

clibanarii, recalling traditional links with the Greco-Roman world). Ammianus

describes the draco standards carried in Constantius’ procession (this one copied

from a specimen found at Carnuntum in Pannonia Superior) as having shafts encrusted

with precious stones: ‘he was surrounded by dragons, woven out of purple thread

and bound to the golden and jewelled shafts of spears (dracones hastarum aureis

gemmatisque summitatibus inligati)’.

Second

Half of the 4th Century AD

(1)

Catafractarius, battle of Argentoratum, AD 357

The

heavy cavalrymen painted in the catacombs of Dino Compagni (Via Latina), from which

we reconstruct this mailed rider, still show at the time of Constantius II and

Julian the use of old types of masked helmets with eagle protomes, of the Heddernheim

or (as here) Vechten types. Interestingly, this man carries javelins with barbed

heads, which are represented on some stelae of catafractarii, like that of

Klaudianus. Catafractarii, in contrast to clibanarii, are often represented with

the wide shield of the scutarii.

(2)

Clibanarius of Vexillatio equitum catafractariorum clibanoriorum; Claudiopolis,

c. AD 350

We

are able to reconstruct quite a good image of richlyequipped cataphractarii and

clibanarii from iconography together with descriptions in the sources (Pan. IV,

22; Amm. Marc. XVI, 10, 8; Jul. Imp., Or. in Constantii Laudem, I, 37ff ). The predilection

of Constantius II for such troops is attested by the numerous regiments raised

by him, and quoted in his funerary oration pronounced by Julian. The

reconstruction is based partially on the Dura Europos material, but note the

ridgehelmet prefiguring the famous 7th-century Sutton Hoo

Germanic

specimen; this fits well with a description of clibanarii wearing face-mask

helmets (‘personati’). Claudian, in his Panegyrics, describes the distinctions

of the armoured cavalrymen of the Imperial retinue: sashes around the waist, peacock

feathers on the helmet, and gilded and silvered cuirasses and shoulder-guards.

Iconography attests the use of the old-style Roman ‘four-horn’ saddle at least

into the first

half

of the 5th century.

(3)

Clibanarius of Schola scutariorum clibanariorum; Constantinople, AD 380

For

this man we have used a specimen of heavy cavalry helmet of ridge type, and a

blazon for his small shield copied from the Notitia Dignitatum (in which the

heavy cavalry’s use of battle-axes is also attested). The striking appearance

of the clibanarius is noted by Claudian describing the army in Constantinople

on 27 November AD 395: ‘It is as though iron statues moved, and men lived cast

from that same metal’. On that occasion he mentions plumed helmets (cristato

vertice), and armour of flexible scales or laminae fitted to the limbs (conjuncta

per artem flexilis inductis animatur lamina membris).

The

West, 5th Century AD

(1)

Catafractarius of the Comites Alani; Mediolanum, Gallia, AD 430

The

cavalryman is reconstructed from Romano-Sarmatian archaeology in Gallia and

northern Italia, also incorporating elements from Pontic finds. These units served

under the Magister Militum in Italy, according to the Notitia Dignitatum, which

gives us their shield blazon. The man is armoured with bronze squamae of Roman

typology, and armed with the contus and long Pontic sword; a specimen of the

latter is decorated in the cloisonné style of Constantinople fabrica. Hidden

here on the far side of his saddlery is a composite bow and quiver of arrows.

The Alani reportedly used the flayed skins of their slain enemies to make horse

trappers, and the faces were hung from the horse’s antilena. This rider is

using the new type of nomad-style saddle with raised saddlebows front and rear

in place of the old four pommels.

(2)

Clibanarius of Galla Placidia’s buccellarii, c. AD 425–450

Bucellarii

were personal units raised by an individual rather than the state; the

politically active Galla Placidia was the daughter of Theodosius I (r. 379–395),

and acted as regent for Valentinian III from 423 to 437. The cavalryman is

largely copied from the mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore. Besides a cuirass of

iron lamellae he wears an early example of ‘splint’ armour on his exposed right

arm; similar armour has been found in Abkhazian graves of the 5th century,

where warriors

were

buried with Eastern Roman military equipment. Such specimens have long splints

on the outer arm and shorter ones partially covering the inside, over a leather

support fastened with buckles; below them and attached by two large rings are

hand-protectors of ringmail. Padded leg protection of felt and coarse silk covers

the legs down to the shoes, fastened behind with laces and buckled straps.

(3)

Clibanarius of Equites clibanarii; Cirta, AD 400

This

trooper is equipped for training. A mosaic at Cirta (Constantine, Algeria) shows

cavalrymen of the Western Empire training with javelins and riding caparisoned

horses (see Osprey Campaigns 84, Adrianople AD 378, p. 6. Man and horse are

protected with quilted armour of an organic material, in the rider’s case

probably corresponding to the thoracomacus worn under the heavy armour of the

clibanarius. The vestitus equi of his mount may, by contrast, be actual war gear,

comparable to those represented on the lost Column of Arcadius and Theodosius.

If made with felt padding this kind of caparison would give protection against

low-velocity, longrange missiles.

The

East, 5th Century AD

(1)

Cataphractarius of Schola scutariorum secunda or Schola armaturarum seniorum,

AD 400

The

fragments of the lost Column of Arcadius and Theodosius, and the

Renaissance-period Freshfields drawings of it, show the lavish equipment of

Eastern Roman cavalrymen of the Imperial Guard. Shield blazons engraved on the

Column pedestal confirm the presence of the cavalry Scholae Palatinae and Domestici

Protectores on the battlefield, armoured with ‘muscle’ cuirasses in metal or

leather, and laminated limb armour over ringmail. Claudianus describes the

Eastern Roman cataphracts wearing helmets with peacock-feather plumes, and wide

red sashes around the body, as signs of their status or unit. Masked helmets

with human faces (personati) were still employed by cavalrymen, often decorated

in red leather; the Column shows the use of both male and female masks. This

last example in Roman art of the use of masked helmets in battle is confirmed by

the almost contemporary specimen from Sisak. The written sources also mention

units of heavily armoured mounted archers, anticipating the further evolution

of the Roman heavy cavalry in the 6th century.

(2)

Catafractarius of the Equites catafractarii Albigenses, AD 400–425

This

man is reconstructed from the grave of a cavalryman found on a Balkan

battlefield with all his armour. Besides a ridge-helmet, he is protected by a

ringmail lorikion, laminated armour on his arms, and thigh protection above his

greaves. Apart from the contus, he is armed with a long spatha.

(3)

Leontoclibanarius; Aegyptus, AD 450–500

This

Egyptian cavalryman has a helmet of Romano-Sassanian style, fitted with a mail

hood aventail which leaves only the eyes uncovered. He wears on his neck and

upper breast an early example of scale peritrachìlion, and below this his trunk

is covered with a combination of ringmail and scales recalling Iranian styles. Again,

his limbs are protected by articulated plates. His weapons again include a

battleaxe. Dtinsis (see Bibliography, under Diethart) suggests that the unit’s

symbol was a leonine motif which the Notitia Dignitatum shows, perhaps on a

small cheiroskoutarion shield. The horse’s neck and forequarters only are

armoured partly with bronze scales and partly with padded material

(κέντουκλον). Note the chamfron in felt with metallic appliqué, copied from a

unique specimen in the Berlin Museum.