1. FORDING TO BATTLE, 10:30 HRS

The train (1) is being organized and will hang back close to the ford. The single battalion

(2) of regiment Huchtenbroek marches off to join the other units ready for battle on the

beach. The men march in step, part of their drill. Because the enemy is near, the unit

marches in close order, each men occupying 3ft by 3ft (90 x 90cm). For longer marches in

battle order, the formation would open up, usually to 6ft (180cm) between ranks only.

Regiment Brederode (3), also a single battalion, is the last across. It fords as a march

column, i.e. first the right hand shot sleeve, then the right half of the pike block, then the

left half and finally the left hand shot sleeve. No matter the size of the unit (4), Republican

foot would always deploy in ten ranks. Sergeants were usually posted on the sides.

Captains (5) had to stay between the enemy and the unit. Lieutenants (6) were on the

opposite side. The unit’s field commander (7), often the lieutenant-colonel, rode in front,

accompanied by his company’s drummers. The other drummers (8) stayed behind the

unit. The second in command, often the major, would lead the second battalion, or if the

regiment only fielded one, stay behind it. If a regiment deployed both its battalions next to

each other, the commander would be in the gap between the two, with his company’s

drummers and banner, precursor of the regimental banner.

The regiment still has calivermen (9), they form the flank files of the shot sleeves. The

musketeers were placed closest to the pikes. The unit looks quite uniform: the men were

supplied from general stores, including their clothing. All armour (10) was blackened.

Commanders were usually armoured like a cuirassier. The first two ranks of pikemen had

extra armour on shoulders, upper arms and thighs. Regulations existed even for banners.

They had to show the Republic’s red lion, and all banners of a regiment had to use the

same colours. Huchtenbroek's and Brederode’s are unknown, but Brederode was a

regiment from Holland and both the arms of Brederode and Holland were the same as the

Republic’s official arms: a red lion on a yellow field. The men could take off their breeches

(11) etc. before fording and needed some time to put everything back on again. Notice the

knapsacks (12): every man carried several days of rations.

The train (1) is being organized and will hang back close to the ford. The single battalion

(2) of regiment Huchtenbroek marches off to join the other units ready for battle on the

beach. The men march in step, part of their drill. Because the enemy is near, the unit

marches in close order, each men occupying 3ft by 3ft (90 x 90cm). For longer marches in

battle order, the formation would open up, usually to 6ft (180cm) between ranks only.

Regiment Brederode (3), also a single battalion, is the last across. It fords as a march

column, i.e. first the right hand shot sleeve, then the right half of the pike block, then the

left half and finally the left hand shot sleeve. No matter the size of the unit (4), Republican

foot would always deploy in ten ranks. Sergeants were usually posted on the sides.

Captains (5) had to stay between the enemy and the unit. Lieutenants (6) were on the

opposite side. The unit’s field commander (7), often the lieutenant-colonel, rode in front,

accompanied by his company’s drummers. The other drummers (8) stayed behind the

unit. The second in command, often the major, would lead the second battalion, or if the

regiment only fielded one, stay behind it. If a regiment deployed both its battalions next to

each other, the commander would be in the gap between the two, with his company’s

drummers and banner, precursor of the regimental banner.

The regiment still has calivermen (9), they form the flank files of the shot sleeves. The

musketeers were placed closest to the pikes. The unit looks quite uniform: the men were

supplied from general stores, including their clothing. All armour (10) was blackened.

Commanders were usually armoured like a cuirassier. The first two ranks of pikemen had

extra armour on shoulders, upper arms and thighs. Regulations existed even for banners.

They had to show the Republic’s red lion, and all banners of a regiment had to use the

same colours. Huchtenbroek's and Brederode’s are unknown, but Brederode was a

regiment from Holland and both the arms of Brederode and Holland were the same as the

Republic’s official arms: a red lion on a yellow field. The men could take off their breeches

(11) etc. before fording and needed some time to put everything back on again. Notice the

knapsacks (12): every man carried several days of rations.

2. FIRST CUIRASSIER CHARGE, SECOND LINE, 16:15 HRS

The second lines of the cavalry wings meet in the meadow, during the first cavalry charge

(1). The church tower of Nieuwpoort is visible in the distance (2). The infantry battle is in

the dunes in the upper right corner (3). In the foreground the cuirassier squadron of Paul

Bacx has just threaded its opponent and is facing about to charge the same unit again in

the rear (4), each rider pivots his horse in turn (5). The opposing unit is wheeling away

from the charge to return to its own lines. A wheel takes much longer than an about-face

however. By the time the Royalist unit is halfway through its wheel, the Republican unit will

already have fallen on its rear. Drill made Republican cavalry very controllable. At

Nieuwpoort for example, the two lines of Louis’ first cuirassier charge had rallied back to

their starting line within half an hour.

Paul himself wasn’t present, his unit was commanded by his lieutenant John Six (6).

The three brothers Bacx had been serving the Republic as cavalry captains since the

early 1580s. They all had their own squadron. Marcel led a cavalry field regiment at

Nieuwpoort. Paul was away, governing Bergen op Zoom. John, the eldest and most

experienced, led his squadron as part of Solms’ regiment (John was married to ‘one of the

prettiest women of Holland’, the sister of colonel Huchtenbroek, himself once cornet of

Paul). The enemy squadron might be the German cuirassiers of Christopher John Count

of Salm-Rijferscheydt, a military family on the other side. He was severely wounded,

probably during this charge. He was taken to Ostend where he succumbed to his wounds

on 26 August, 26 years old.

Christopher’s unit wears the traditional cassock, often red in the Royalist army, Paul’s

men wear the regulation blackened armour and orange sash. Armour was blackened to

prevent rust. A mixture of linseed oil and soot was applied and then heated, leaving a

permanent black layer. More expensive methods left the metal brownish or bluish. The

pole of a cuirassier banner was usually carried in a cup near the foot and held upright with

a loop around the arm, so the rider was free to fight (7). This reconstructed banner shows

the Bacx arms. The men in Republican front ranks were better armoured. Cuirassiers

charged with their swords. Pistols were used for continued melee and pursuit.

The second lines of the cavalry wings meet in the meadow, during the first cavalry charge

(1). The church tower of Nieuwpoort is visible in the distance (2). The infantry battle is in

the dunes in the upper right corner (3). In the foreground the cuirassier squadron of Paul

Bacx has just threaded its opponent and is facing about to charge the same unit again in

the rear (4), each rider pivots his horse in turn (5). The opposing unit is wheeling away

from the charge to return to its own lines. A wheel takes much longer than an about-face

however. By the time the Royalist unit is halfway through its wheel, the Republican unit will

already have fallen on its rear. Drill made Republican cavalry very controllable. At

Nieuwpoort for example, the two lines of Louis’ first cuirassier charge had rallied back to

their starting line within half an hour.

Paul himself wasn’t present, his unit was commanded by his lieutenant John Six (6).

The three brothers Bacx had been serving the Republic as cavalry captains since the

early 1580s. They all had their own squadron. Marcel led a cavalry field regiment at

Nieuwpoort. Paul was away, governing Bergen op Zoom. John, the eldest and most

experienced, led his squadron as part of Solms’ regiment (John was married to ‘one of the

prettiest women of Holland’, the sister of colonel Huchtenbroek, himself once cornet of

Paul). The enemy squadron might be the German cuirassiers of Christopher John Count

of Salm-Rijferscheydt, a military family on the other side. He was severely wounded,

probably during this charge. He was taken to Ostend where he succumbed to his wounds

on 26 August, 26 years old.

Christopher’s unit wears the traditional cassock, often red in the Royalist army, Paul’s

men wear the regulation blackened armour and orange sash. Armour was blackened to

prevent rust. A mixture of linseed oil and soot was applied and then heated, leaving a

permanent black layer. More expensive methods left the metal brownish or bluish. The

pole of a cuirassier banner was usually carried in a cup near the foot and held upright with

a loop around the arm, so the rider was free to fight (7). This reconstructed banner shows

the Bacx arms. The men in Republican front ranks were better armoured. Cuirassiers

charged with their swords. Pistols were used for continued melee and pursuit.

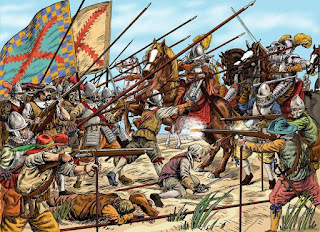

3. LAST STAND, 18:30 HRS

On the beach, (1) a cuirassier troop from Balen’s field regiment mops up the last

resistance. Most of his cuirassiers had moved into the dunes to ride down anyone left in

the valleys. Unaware of their presence, the depleted pike block of Spanish regiments Villar

and Zapena fell victim to them. Closer to the beach, the depleted pike block of Spanish

regiments Maiolichino – the Diest mutineers – and Monroy had witnessed the destruction

of one of their detachments by the cuirassiers. They had time to separate into two or more

smaller units and move onto dunes, where they were safe from hooves and sabres, but

isolated and without most of their shot. The Frisians of regiment W. Nassau were ordered

to attack them. Like most infantry in the Republican army they had split into half-battalions,

better suited to take and hold individual dunes. Here the pikemen of one of these, perhaps

250 men strong, assaults the last stand of the mutineers and some of Monroy’s men. The

soft sands and steepness of the dunes presented yet another challenge, especially for the

pikemen who had a hard time presenting a solid front. Pole-arms as wielded by the

officers (2) must have been especially effective in these circumstances.

The uniform appearance of the Republicans contrasts with the individuality of the

Royalists, who included many demoted officers, euphemistically called ‘reformed’, and in

this formation many self-enriched mutineers. Comments mention that Spanish soldiers

hadn’t much money on them, but did wear fine clothes and an abundance of jewellery.

Little mercy was shown on this side of the battlefield where the mutineers fought, because

they were held responsible for the massacres at Snaaskerke and Mariakerke. Most of the

Spanish dead remained unidentified, including most of the (reformed) officers: there

simply was no one left from their unit to recognize them (3). Notice the heavier armoured

front ranks of the Republican unit. The banners shown on the left are – from left to right –

Ripperda*, Aernsma and Blauw* . They’re from the sketchbook of the secretary of the

regiment. This is the first time ever they’ve been published in colour. The banners on the

right are the blue mutineer banner depicted elsewhere in the book and two banners from

Bassen’s painting of captured flags, also depicted elsewhere. (*these have erroneously

been switched in this book with Sageman and Grovestins depicted elsewhere).

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario